As many of you know, I recently attended the Second World Congress of Clinical Neuromusicology in Vienna. Though there were many intriguing presentations, one presentation in particular stood out. In 1996, Dr. Gottfried Schlaug (Boston, Harvard Medical School) performed an experiment to test the shared neural correlation of singing and speech. A portion of the abstract follows:

Using a modified sparse temporal sampling fMRI technique, we examined both shared and distinct neural correlates of singing and speaking. In the experimental conditions, 10 right-handed subjects were asked to repeat intoned (“sung”) and non-intoned (“spoken”) bisyllabic words/phrases that were contrasted with conditions controlling for pitch (“humming”) and the basic motor processes associated with vocalization (“vowel production”) (Özdemir, Norton, and Schlaug, 2006).

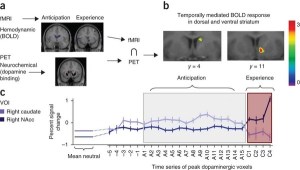

The remainder of the paper may be found here, but I will try to summarize the result. Basically, by actually singing the words or phrase, and not simply speaking or humming (referred to as ‘intoned speaking’), there occurred additional right lateralized activation of the superior temporal gyrus, inferior central operculum, and inferior frontal gyrus. What this means for the rest of us? This activation is now more than ever believed to be reason that while patients suffering from aphasia due to stroke or other varying brain damage may be unable to speak, they are able to sing.

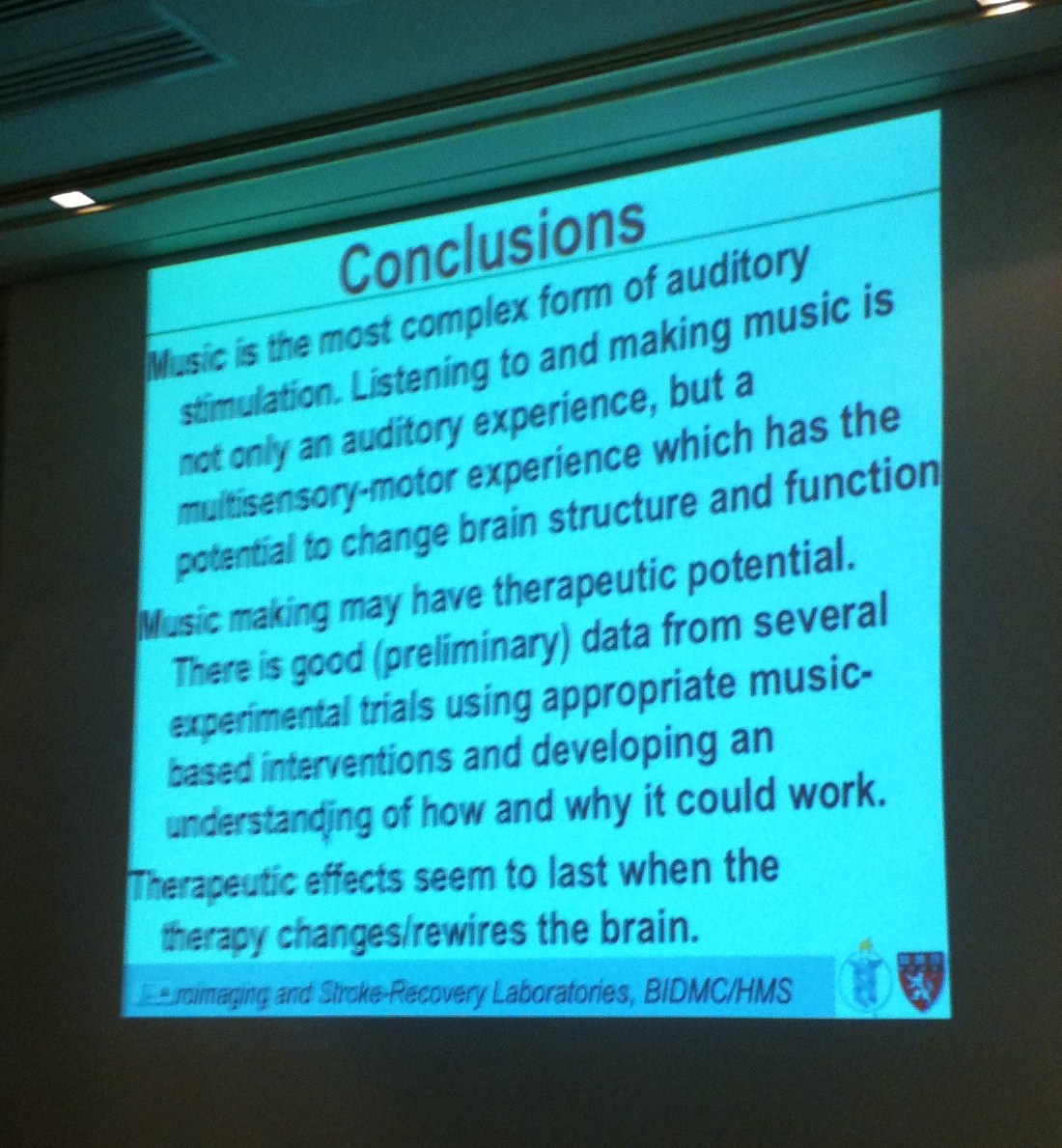

That was in 2006. In a few short years, music therapy and the applied neuroscience of music have all but exploded-the question is, why? As many publications have noted, the idea that music can be used in rehabilitation has been around for a century or more. So what has caused such media coverage in the last few years? My simple theory is because through the popularization of these techniques’ success via persons in the public eye, everyone is beginning to understand that it just works.

Speaking of the public eye, a friend sent me this article from NPR this morning. Though I was vaguely familiar with this success story, it really surprised me to see it mentioned in national media. For those unaware, a current hot topic in science journalism is the method of therapy Gabrielle Giffords has chosen after she suffered massive brain trauma. I’ve run into cases similar to this one before, but it was what kind of music therapy that really caught my attention: Melodic Intonation Therapy. The reason this really caught my attention is because this is precisely the groundbreaking (and very successful) research Dr. Schlaug presented at the conference in Vienna, only his use was with nonverbal Autistic children. Though Schlaug’s research largely pertains to other faculties, he set out in this case to test AMMT (Auditory Motor Mapping Therapy, a kind of specifically targeted ASD therapy akin to Melodic Intonation Therapy used for stroke patients with aphasia) against normative Controlled Speech Therapy.

Without going too in-depth, what he and his team discovered was that patients who engaged in singing (as opposed to merely speaking or humming) showed additional right lateralized activation of the superior temporal gyrus, inferior central operculum, and inferior frontal gyrus. Due to this, a strong case can be made as to why aphasic patients with left-hemisphere brain lesions are able to sing the text of a song whilst being incapable of speaking the same words. What this means for the whole of this ‘Singing Therapy’ is that by being able to work with brain regions such as Broca’s area which may facilitate the mapping of sound to action, all kinds of different strides may be made linguistically in patients with left-hemisphere brain damage. People who suffer from neurological impairments or disorders that would otherwise be completely unable to communicate verbally may now have that chance. In the words of Dr. Schlaug, “When there is no left hemisphere, you need the right hemisphere to work.”

To get back to congresswoman Giffords, I’d like to take a moment to talk about what is so important and unique with her situation by looking at her case from point of impact to recovery. Nearly one year ago, Giffords sustained a massive head trauma via a bullet that went directly through her brain. Unfortunately, when the bullet entered in this way, it didn’t stop at destroying the tissue in its path (which was for her in the left hemisphere); it also damaged the surrounding neurons, causing the brain to quickly swell and put her in immediate fatal danger of hematomas and other complications. Because of this, surgery was necessary right away to remove a portion of her skull in order for the swelling to, as it were, breathe. The surgery Giffords took part in was the once risky decompressive hemicraniectomy. For more information on this procedure, there’s a fantastic post by Bradley Voytek over at Oscillatory Thoughts including some great data, analysis and images on the process. If the congresswoman’s circumstances are ringing any bells for anyone, it’s because it bears some resemblance to arguably one of the most famous head trauma cases in neuroscience and psychology as a whole-Phineas Gage. I shall soon share some thoughts on Gage, and why he remains so near and dear to my heart (and certainly to the heart of Antonio Damasio) in terms of emotional intelligence and neuroscience, but until then, some parting thoughts on Giffords.

In the beginning of this road to recovery, most were skeptical that Giffords would ever be able to speak again, in any vein. However, through the process of working in Melodic Intonation Therapy with her music therapist, she has gone from singing short words and phrases (in minor thirds, the prominently used interval in this therapy) to singing Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star to more structurally complex and well-known jazz and rock standards such as I Can’t Give You Anything But Love and American Pie. She has made massive strides in her recovery process, and continues to make more every day. This is only one example of the effectiveness and hope this “Singing Therapy” is bringing to the medical field. Even after speaking to Dr. Schlaug inVienna and finding he has “absolutely no interest whatsoever” in psychological disorders, I continue to be enthusiastic in the strides he and his team are making in the applied neuroscience of music.

A note: I continue to be amused by what a small world the pragmatic combining of music and neuroscience remains. Upon reaching the end of the NPR article, I now know why it was already so familiar to me, and why I immediately thought of Schlaug’s work at Harvard and Beth Israel-it is because that’s precisely the team NPR is taking their data from! Brilliant.

You must be logged in to post a comment.