We accept the love we think we deserve

How does one interpret reality? Psychologically speaking, one may take a number of viewpoints. Countless factors come to play, first and foremost being the common argument of ‘nature or nurture.’ Aspects such as religion, race, culture, gender, sexuality, economic status, and mental health history can all work together to create vastly differing versions of reality. In stories, “narratives help us impose order on the flow of experience so that we can make sense of events and actions in our lives. They allow us to interpret reality because they help us decide what a particular experience ‘is about’ and how the various elements of our experience are connected.” (Foss, 399).

When someone reads a story, listens to a song, or watches a film, what determines their overall opinion and stance on what has transpired? As we mature from children into adolescents and adults, our methods of discernment have the capacity to shift radically. Not only upbringing and the norms of childhood, but also life experiences contribute to the process of modification in how one perceives their world.

Many narratives are chronologically organized, that is, organized in a time-observant sequence of events, while others may focus more on a specific character or theme. Narratives may come in the form of graphic novels, films, television, conversation with others, speeches, short stories, graffiti, music and other folklore. The use of symbols throughout the different forms are what arguably best categorize them as such, and to demonstrate this, I’d like to look at a poignant and inspiring ‘coming of age’ narrative entitled The Perks of Being A Wallflower. How does one interpret reality; but even more importantly, how is the construction of a narrative used to determine how we interpret reality?

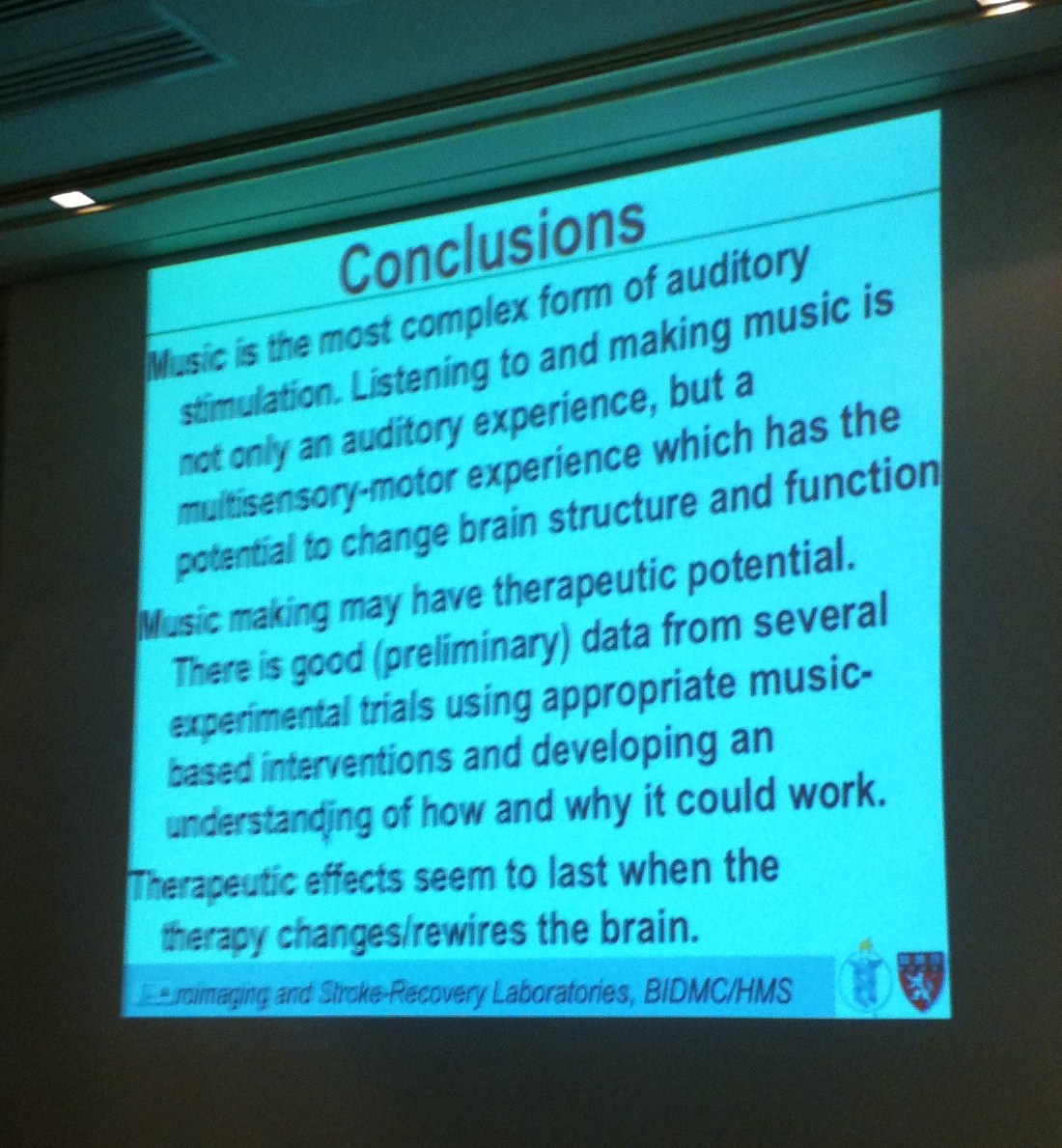

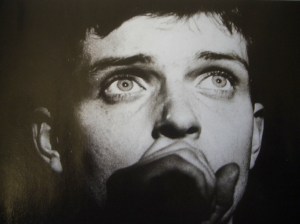

Set in Pittsburgin the early 90s, Stephen Chbosky’s The Perks of Being a Wallflower is a story of the transformation of desperate introversion in an extroverted high school universe. Throughout the novel, the protagonist Charlie anonymously writes letters to an undisclosed recipient detailing the meaningful and turbulent journey through his freshman year. As the narrative begins, Charlie’s best (and only) friend has just committed suicide. Due to this, Charlie’s introversion and acute timidity as a new student are greatly challenged as he meets a spectrum of new friends along the way, not least of all, his English teacher Bill. As his relationship develops with this mentor, he is introduced via his surroundings to music, literature, love, sex and drugs. Throughout the novel, the reader is constantly subjected to perceptions of reality from many different perspectives. Sam, the beautiful and popular but taken woman of Charlie’s affection, her gay stepbrother and Charlie’s new best friend Patrick, and others including his family and peers make up the vastly different interpretations that all come together to challenge and question Charlie’s previously understood ideas and worldview. As Charlie as introduced to new musicians like The Smiths, Ride, Nick Drake, Smashing Pumpkins, Nirvana, U2 and Nat King Cole, his journey becomes increasingly personally psychoanalytic as he learns to relate, in one way or another, to these musicians.

To begin analysis, I’d like to start by looking at our main question: how does the author use the narrator and protagonist’s surroundings and cultural arena to construct a perception of reality? Charlie begins his textually prominent setting of high school in the immediate aftermath of an incredibly traumatic event: losing his best and only friend to suicide. Not only do we commence our journey in what is known already to be a daunting period, we also begin through the eyes of a painfully shy boy who is emotionally damaged and alone. Our opening and lasting impression of him describes the death of his favorite aunt, and later in life, dear friend.

Throughout the first portion of our novel, we see Charlie’s more intellectual habits develop-the way he rereads books twice to more fully understand them; the way he accepts all the extra essay assignments from his English teacher (and later mentor) Bill with a vigor. In the beginning, our perception of reality is formed through the eyes of an overachieving boy who simply wants to get through, and possibly fit in. His definition of reality is one of survival-of holding it all in as long as he possibly can.

The second way we are introduced to his existence is the mode in which he meets new people. Through his surrounding of stronger, more single dimension characters such as Sam, Patrick, his family and teacher Bill, we are shown how Charlie slowly enables himself to become a somewhat social being. In a largely stable environment, however, Charlie remains the wildcard, frequently being prone to crying over what is termed “silly things” and repressed feelings of guilt from the tragic death of his aunt in particular. The deeper in to the narrative we go, the more objective our surroundings seem, and the more subjective Charlie’s character dimension and experience prove. As a deliberately vague description of what happened between his aunt and he at a young age reappears throughout the work, we begin to slowly understand this trauma has played a far larger role in shaping who he is than previously thought. It is himself, and his aunt that prove to be the most round and conflicted characters of the narrative, thus allowing them the greatest space for growth. Charlie is a radically dynamic figure growing in knowledge, experience, and maturity more and more until he finally accepts his loss of innocence.

Another way we can examine Charlie’s social worldview is by asking what parts of his culture are privileged, and what parts are repressed. Through Charlie’s friend Patrick’s secret homosexual relationship with the quarterback of the football team, Charlie’s heightened embarrassment over his frequent display of emotion in crying and his family’s unrealistic expectations of Charlie’s older brother’s college success, we may see his culture is not too far from our own. The ‘popular’ kids in school remain those in financially advantageous situations; the outcasts remain the quiet or socially awkward. In Charlie’s world, blending into the crowd is desirable, while individuality and deviance is highly discouraged. In this way, Sam is able to retain a strong sense of acceptance due to her beauty and class status, while her brother falls socially down when word gets out of his sexual identity. What this says about their system of ethics is that the patriarchy reigns. The privileged prevail while the less privileged do not. The beautiful thing in Charlie’s developing social situation is that these lines become more and more blurred as he is able to find true acceptance from the outcasts and privileged alike.

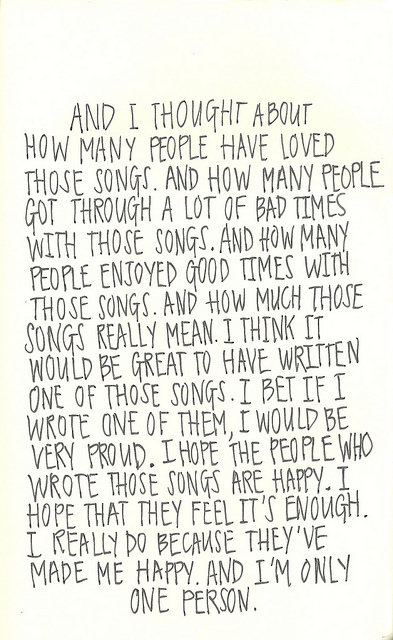

Lastly, I’d like to talk about Charlie’s point of view as narrator. Chbosky has given Charlie a very human and humble tone, beginning quietly and ending more confidently. As the overall theme of the work is coming of age, loss of innocence and psychological resilience, it should be noted what Charlie learns, and most importantly, what he realizes in the end. As a child, Charlie was repeatedly molested by his favorite aunt. He only comes to understand this in the final pages-in the epilogue, no less. Through all of his pain, loss and personal turmoil, Charlie tells us a story of hope through friendship, love and music, how to get by in the tough world of adolescence, and the upside of being a wallflower. Charlie is not omniscient or omnipresent-he is just a boy, trying to figure out how to become a man. In Charlie’s indirect narration, we are shown a world of people who are tangible and relatable to every era. His story is trustworthy, reliable and raw. By the sense of established confidence in Charlie’s letters, we are shown a brilliant world of living splendidly through trial.

In conclusion, applying a narrative criticism best illuminates this artifact because it allows the reader and critic to more closely examine what is revealed about the individual’s or culture’s identity. It allows us to ask probing questions into their worldview and motives for action by looking at subjectivity in character dimensions. Narrative criticism enables one not only to analyze the content of the worldview, but the form and structure of that worldview as well. By looking deeply into the sexual and emotional trauma Charlie has undergone, by looking at all of the external factors including ethical, cultural, religious (or lack thereof), social, economical, and intellectual combined with his internal processing revealed to us by the author, we can truly appreciate what constitutes this hopeful ‘reality’ our protagonist has found.

Rhetorical Criticism: Exploration and Practice. Ed. Sonja K. Foss. Prospect Heights: Waveland Press, Inc. 1996.

You must be logged in to post a comment.